Convalescent plasma has been used as a treatment for viral infections for over a century, beginning with the 1918 flu pandemic. More recently, it was used during the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic, the 2014 Ebola outbreak and then the coronavirus pandemic.

Engaging convalescent plasma in the fight against COVID-19 was first proposed in February 2020 after a small study found that convalescent plasma was safe and effective in treating patients with the virus. In April 2020, Jonathan Gerber, MD, was the first person in Massachusetts to use convalescent plasma to successfully treat a seriously ill COVID-19 patient. He ran a convalescent plasma treatment program at UMass Memorial Medical Center that ultimately treated more than 500 patients.

“Early on, it was one of the very few treatments we had available,” said Gerber, Professor of Medicine, Chief of the Division of Hematology & Oncology, Medical Director of the Cancer Center, and Eleanor Eustis Farrington Chair of Cancer Research at UMass Chan Medical School and UMass Memorial Health.

Benefits of convalescent plasma

While some early research performed elsewhere reported mixed results, Gerber was a co-author of a large study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in March 2022, that showed clear benefits of COVID-19 convalescent plasma. UMass Chan Medical School participated in the multicenter, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial, which was funded by the U.S. Department of Defense and led by Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

This early-treatment study was conducted between June 2020 and October 2021. Participants included 1,181 randomized patients who received one dose each of either polyclonal high-titer convalescent plasma or placebo control plasma within eight days of having tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Patients treated with convalescent plasma had a 54% reduction in their risk of having to be hospitalized compared to those receiving placebo plasma. Adverse outcomes were minimal and not different between convalescent and control plasma. Of the 592 patients who received convalescent plasma, 17 (2.9%) were hospitalized within 28 days of their transfusion, compared with 37 of the 589 (6.3%) who received “placebo” control plasma.

Low-tech solution, highly effective results

Another significant outcome of the study was that a relatively low-tech and widely available solution could provide effective results on par with much more sophisticated treatments that take months or years to develop. The discovery could have global impacts.

“For countries that do not have the infrastructure or funding for high-tech lab research, collecting convalescent plasma is more possible than developing and manufacturing monoclonal antibodies,” said Gerber. “This is one of the great advantages of convalescent plasma treatment.”

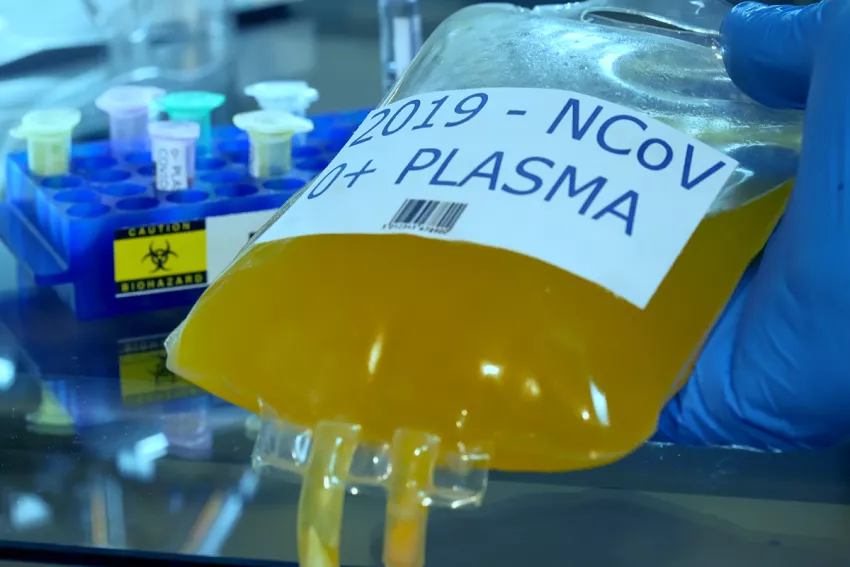

Convalescent plasma is collected from people who have recovered from infection and contains antibodies that can help fight the disease. Naturally made antibodies prevent the need for and cost of developing antibodies in a laboratory, which requires meeting quality control standards, navigating regulatory hurdles, and then manufacturing the antibodies.

“We can collect blood a couple of weeks after a patient recovers from the virus, confirm the antibody levels are high, perform standard blood donor testing, and separate the plasma using an old-time centrifuge,” said Gerber. “Then it’s ready for use.”

Convalescent plasma also provides a wide array of antibodies that may attack multiple targets in the virus.

“Monoclonal antibodies are like a sniper shot,” Gerber said. “They’re effective against a very specific target on the virus. Polyclonal antibodies — like those found in convalescent plasma — attack multiple targets in a virus.”

The advantage, he said, is that if the virus does mutate, there’s a chance it will still have a target that some of the antibodies are effective against.

Barriers to using convalescent plasma

For all the advantages of using convalescent plasma, persistent barriers hinder its widespread use in treating COVID-19 or any other virus.

“The cost of collecting and testing blood can be prohibitive,” said Gerber. “Also, when we first started using plasma, the cost was subsidized by the federal government. Other treatments are still being subsidized, but convalescent plasma is not.”

An enduring stigma against blood transfusions can also create an impediment for patients who would be good candidates for convalescent plasma therapy.

“There continues to be a perception that there is risk of contracting blood-borne diseases through blood transfusion,” said Gerber. “Some people feel more comfortable receiving a monoclonal antibody developed in a lab, rather than receiving plasma.”

However, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mandates that all blood collected for transfusion is tested for the presence of specific infectious disease pathogens, such as hepatitis B and C viruses and HIV.

“Statistically speaking, the risk is vanishingly small. A person is more likely to get struck by lightning than contract HIV or hepatitis C from a blood transfusion. However, the anxiety persists,” said Gerber.

The future of convalescent plasma

Despite the obstacles, Gerber remains optimistic about the future use of convalescent plasma.

He believes that, as COVID-19 evolves and produces more resistant strains, there will continue to be opportunity to use convalescent plasma as an early treatment while waiting for the next monoclonal antibodies or antiviral to be developed and distributed.

“There are all kinds of economic and health benefits to using convalescent plasma, certainly in less developed countries, but also in the U.S. where using it can help prevent overcrowding in our hospitals — especially our ICUs,” he said.

While convalescent plasma may not be a panacea, Gerber said it’s important for health care providers to “keep it in the toolbox” for when other treatments are not available or effective.

“It may be a very powerful weapon against illnesses we don’t even know about yet.”

View more stories of healing, advancing medicine and innovating from UMass Memorial Health.