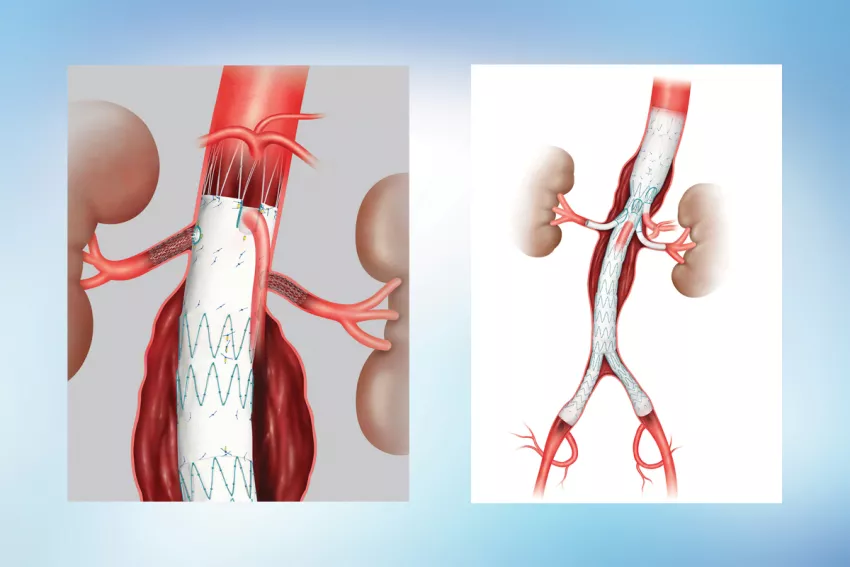

Photo above: These illustrations show how stent graft devices are placed to repair abdominal aortic aneurysms.

A 2021 New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) article on managing abdominal aortic aneurysms provided evidence in support of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) over open repair, as well as a review of formal guidelines and clinical recommendations.

The study was authored by Andres Schanzer, MD, FACS, Chief of the Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery and Director of the Center for Complex Aortic Disease at UMass Memorial Medical Center, and Gustavo Oderich, MD, Professor and Chief of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery at McGovern Medical School, UTHealth Houston.

“There is the need to balance the risk of observing an aneurysm against the risk of repair,” said Schanzer, who is also Director of the UMass Memorial Health Heart and Vascular Center and a Professor at UMass Chan Medical School. “Then there’s the need to evaluate the risk of open repair or EVAR.”

Common risk factors

A variety of factors increase risk for abdominal aortic aneurysm: advanced age, family history, previous or current use of tobacco, hypercholesterolemia and hypertension. Patients with diabetes mellitus, on the other hand, have a lower risk.

Men are at higher risk than women, and recommendations for when to repair an aneurysm differ for the sexes. An aneurysm with a diameter of 5.5 cm or more makes a man a candidate for repair. For women, a measurement of 5.0 cm or greater should be repaired. Smaller aneurysms may be watched over time to see whether and how much they are expanding and evaluated for level of increased risk.

Benefits of EVAR over open surgery

The NEJM study identifies the benefits of repairing via EVAR rather than open surgery, as found in randomized, controlled trials.

- There’s a lower risk of perioperative complications and death.

- It’s advantageous for the first two to three years after surgery. Longer term survival is comparable to open surgical repair.

- Reinterventions may be more necessary after EVAR, but they usually involve minor endovascular procedures. There is higher risk of a need for laparotomy after open repair.

EVAR patients must be followed long-term with duplex ultrasonography or computed tomographic angiography.

Limits to the procedure

While EVAR patients have a better survival rate than open repair patients at first, the study shows that the gap in the survival rate closes after two to three years. Several reasons are given:

- Underlying cardiovascular risk

- Lack of adherence to follow-up care recommendations

- Ongoing inflammation due to the fact that the aneurysm stays intact with EVAR

- Sac pressurization

- Failure of the stent graft device

In many EVAR cases — 18 to 63% — the patient’s anatomy did not match the manufacturer’s guidelines for appropriate use. While the majority of aortic aneurysms are now treated with EVAR procedures, there are limits to when and how the stent grafts can be used. The devices must match the anatomy of the specific patients to ensure the aorta has healthy areas above and below the aneurysm to ensure the stent graft can be sealed to its wall. The diameter of the femoral and iliac arteries must be large enough for insertion of devices. To avoid the risk of embolization, the patient cannot have excessive plaque and must have vessels that branch within the angle that can be accommodated by the device.

The size, shape, and fenestrations must match the patient anatomy exactly, which can be a challenging goal to achieve with physician-modified stent grafts.

“In my opinion, if an appropriate company-manufactured device is available, that is likely the best option,” Schanzer said, adding that the manufacturer’s quality assurance capabilities are much greater than what can be done when a physician is modifying a device. When working with a stent manufacturer, he and his team make a 3D model of the patient’s aorta and look at other images in comparison to the model. They measure each angle to ensure they understand how the stent graft will interact with the aorta. Then the information is sent to engineers who develop a final model for the manufacturer.

He cautions against pushing the limits of the devices too far, a situation he sees becoming more common in recent years.

“About 25% of our patients are referred to us after failure of their prior EVAR or TVAR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement] procedures,” he said.

View more stories of healing, advancing medicine and innovating from UMass Memorial Health.